When A Bathhouse Learns To Breathe Again: Zeyrek Çinili Hamam

Istanbul is a water city before it is anything else.

Aqueducts stride across highways. Cisterns sit beneath restaurants. Fountains punctuate side streets. The 16th-century Kırkçeşme system, overseen by Mimar Sinan, extended earlier Byzantine supply networks and formalised how water entered, moved through, and sustained the city.

Where water is abundant and engineered, baths follow.

Hammams were not indulgences. They were urban organs — converting water and heat into hygiene, ritual, and collective regulation.

I had heard about a 500-year-old hammam recently restored in Istanbul, with a museum embedded within the complex. Curious to see Zeyrek Çinili Hamam not just as a bath but as a cultural project, I travelled from Athens, where Collections and Programs Officer Tulug Yıldız led me through its layered spaces before I returned to experience it in use.

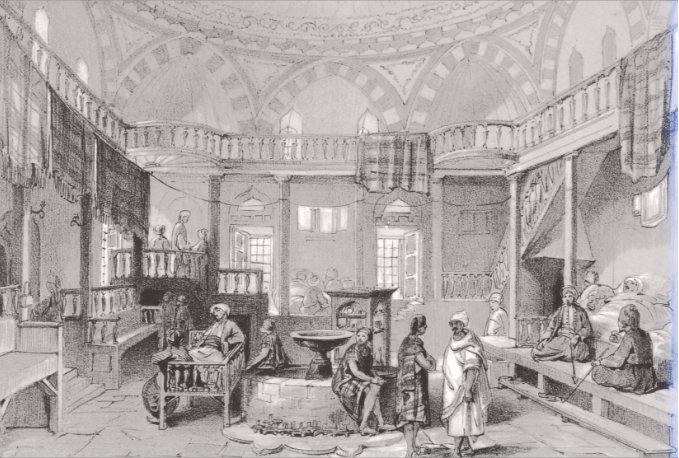

Why hammams proliferated

Following the Ottoman conquest, Istanbul was reorganised through charitable endowments known as vakıf (waqf). These were structured economic vehicles. Revenue-producing assets — shops, markets, inns and baths — funded mosques, schools, kitchens and civic infrastructure.

Hammams were financially rational:

culturally mandated through religious cleanliness norms,

socially embedded as weekly gathering spaces,

and architecturally repeatable.

At their peak, historical accounts suggest hundreds operated across the city. Today, preservation estimates indicate that well over 200 historic hammam structures remain in greater Istanbul, though fewer than 60 function as baths. Many stand closed, altered, or in partial ruin — domes visible above neighbourhood roofs, interiors long stripped.

The typology endured because it was economically embedded and civically necessary.

Zeyrek is one of the rare returns.

Where Ornament Met Everyday Life

Built between 1530–1540, commissioned by Barbaros Hayreddin Pasha and designed by Mimar Sinan, it is a double hammam embedded into the slope of the Zeyrek district — a neighbourhood that today feels suburban and local in scale, yet sits within the UNESCO-listed Historic Areas of Istanbul. When I first visited, the surrounding streets were busy with local shops, children, and delivery vans. The ancient aqueduct handsomely frames the main promenade, and the hammam stands quietly at the end of that main strip.

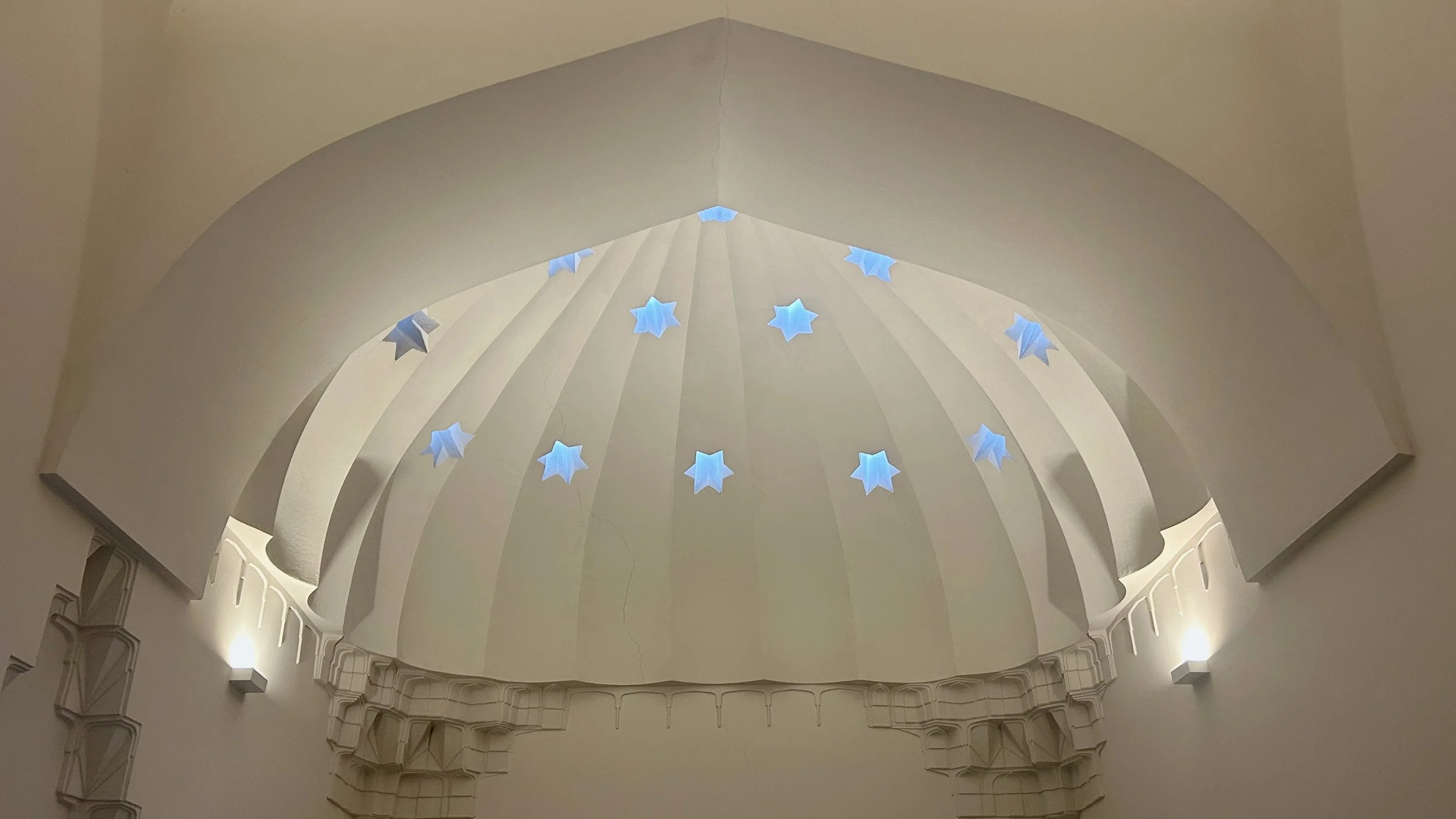

What distinguished Zeyrek historically was its surface. It was richly clad in Iznik tiles — a decorative language typically associated with imperial interiors rather than communal bathing. Fragments recovered during restoration include early blue-and-white floral panels and geometric compositions characteristic of 16th-century production. Over centuries many tiles were removed and dispersed; the museum now digitally reconstructs lost schemes, allowing visitors to read what once wrapped the domes.

Public bathing, here, was dignified and aesthetic.

Restoration as excavation

The contemporary chapter began in 2010, when the Marmara Group acquired the long-closed hammam in 2010, with Bike Gürsel initiating the restoration. The long-closed hammam was bound for a careful restoration under the guidance of a very experienced and specialised development team. Instead, as her daughter and now Founder and Director Koza Güreli Yazgan has shared, “it became like an excavation.”

What was meant to be straightforward conservation unfolded into archaeological discovery: thousands of fragments of Iznik tiles, pottery shards, delicate glass oil bottles, architectural remnants — and, in the Byzantine cistern below, carvings of ships etched into the walls, interpreted as marks left by maritime captives once held there. The building began to reveal not one history, but many.

The museum was not the original ambition; it emerged because the site insisted on it. As artefacts accumulated, interpretation became unavoidable.

And yet, despite the depth of excavation and curatorial development, Zeyrek remains what it was built to be: a functioning hammam.

The Architecture of Care

Entering as a guest, there is the faint smell of orange — subtle, grounding. The surrounding streets hum with local life. Inside, small fold-down chairs in the changing rooms support you as you prepare; attendants guide with attentiveness rather than theatre. Each detail feels calibrated to support you as a visitor. In an annexed bathing chamber, an abstract sculpture of a woman’s body rests quietly. Art is never far away. Marble seating by Athenian artist Theodore Psychoyos has been introduced — sculptural, restrained, contemporary without rupture.

A hammam is, at its core, a heat machine. Underfloor systems channel warmth through stone floors and walls, creating a controlled gradient: cool → warm → hot → return. In a city engineered around water distribution, baths became logical endpoints — converting infrastructure into collective regulation.

Bath + museum + programme

The project now operates simultaneously as functioning hammam, site museum, and cultural venue, with a rotating roster of artists activating the space.

Exhibition design by Atelier Brückner integrates recovered fragments and digital reconstructions with restraint. The cistern below serves as a site for contemporary art installations, extending the narrative rather than fossilising it.

Bike Gürsel’s personal collection of nalın — the wooden bath clogs once worn by attendants, some rising to extraordinary heights — now anchors the museum, forming one of the most comprehensive historic collections of its kind.

As current director Yazgan shared in a recent interview “What may seem like separate experiences—hospitality, heritage, art—have gradually aligned around Zeyrek Çinili Hamam. We kept digging because the story kept unfolding. That pursuit of meaning—that desire to stay with the unknown—was what drove us forward.”

Ruin and potential

Across Istanbul, dozens upon dozens of historic hammams remain closed. Some are structurally intact but economically dormant. Others survive as shells. The city holds a dispersed inventory of bathing infrastructure awaiting either collapse or reinvention.

Zeyrek demonstrates a third path.

Adaptive reuse does not require erasing original function. In this case, bathing remains central. The museum did not replace the hammam; it emerged because of it.

Wellness rooted in civic history

For those of us designing contemporary communal bathing environments, Zeyrek offers a clear lesson.

Baths historically:

were economically structured,

engineered with precision,

and embedded in neighbourhood life.

They were regular public luxuries and necessities.

Standing beneath the domes, orange in the air, marble warm underfoot, you feel the continuity. Water infrastructure becomes social infrastructure. Heat becomes shared regulation.

It is a reminder that wellness, at its most enduring, is civic.